Low Back Pain: Physician Paradigm Shifts and the Doctor of Physical Therapy

Dr. Jessica B. Schwartz PT, DPT, CSCS

What do the common cold and low back pain (LBP) have in common? They are the top 2 symptomatic reasons for primary care visits in the United States (US) [1, 2].

In 1998, total US health care costs for LBP were approximately $90 billion [3, 4]. Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions account for roughly 25% of patient complaints in the primary care setting [5, 6].

In the emergency department (ED), MSK dysfunction accounts for 20% of all chief complaints with 2.7 million visits specifically devoted to LBP [7]. In fact, MSK conditions rank second only to respiratory illness with respect to prevalence of most common presentations in the ED[8].

The intent of this article is to identify global systematic weaknesses in medical education while discussing implementation of best practices as it pertains to low back pain intervention.

My hopes are that by exposing the physician to potential clinical decision and behavioral paradigm shifts that can be immediately implemented, we can reduce cost, increase efficiency, and make our patients feel better quicker.

One thing is for sure: I bet you didn’t learn this in Medical School…

II. Physician Confidence and Competence of MSK Conditions:

It has been recently cited that newly graduated medical students and residents lack the clinical knowledge and confidence necessary to care for patients with MSK injuries. Deficiencies have been shown at all levels of training from medical student to attending [8-11].

Approximately 50% of family practice physicians feel inadequately trained in MSK medicine [8, 12]. There have been similar numbers reported amongst the emergency physician with marked deficiencies in musculoskeletal education ranging from trainees to attending staff[8].

As exposure to MSK conditions increase and physician confidence remains low, we need to address this dilemma head on.

Identification and efforts to improve quality of MSK exposure and future physician education is presently being reviewed and developed[11].

What happens to present day practice in the mean time?

Allow me to take you down a paradigm shift in thinking for the present day physician as it pertains to patient access and prescriptive intervention.

III. Knowledge Translation Gaps:

Clinical Prediction Guidelines (CPGs) have proven to be an excellent tool to meld clinically relevant interdisciplinary conversation via individually competent clinicians.

CPG’s have been copiously produced in an effort to guide a broad range of clinicians along a mutually agreed upon diagnostic pathway. In conjunction with the Choosing Wisely campaign, CPGs combined with 2 of the 3 central tenets of Evidence Based Medicine, doctors should be prescribing fiscally responsible and safe interventions for our patients.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case.

There continues to be overuse of imaging in the emergency and primary care setting despite evidence based recommendations from the American College of Physicians, American Pain Society[4, 13], and the Choosing Wisely Campaign[14].

These organizations call for lumbar spine imaging only for patients who have severe or progressive neurologic deficits or signs and symptoms that suggest a serious or specific underlying condition[13].

Another example of physician knowledge translation failure occurs with the Ottawa Foot and Ankle Rules (OFARs). In a 2014 study of emergency physician application of the OFARs, there was no statistical evidence that application of the OFARs decreases the number of imaging orders. In fact 58 of the 60 patients that qualified under the OFARs were imaged [15]. This observation suggests that even when clinicians are being observed and instructed to use clinical decision rules, their evaluation bias tends toward recommendations for testing.

Unlike the foot and ankle complex, pathoanatomic diagnoses in the lumbar spine is often more detrimental to clinically relevant patient care than not.

Excessive spinal imaging can lead to downstream pathways that can lead to instilling fear of the unknown or “too-much known” into the patient, unnecessary invasive interventions, time lost from work, familial, and social life, and the fiscal burden that all of the above places on government, third-party and private payers.

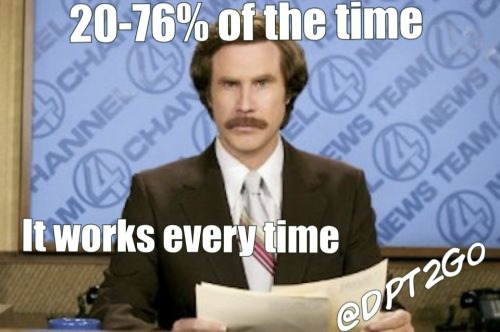

Evidence of false rates of herniated discs are shown on computerized tomography (CT) scans[16], MRI[17], and myelography[18] in 20% to 76% of persons sans radicular pain[19].

Savage et al[20] reported that 32% of their asymptomatic subjects had “abnormal” lumbar spines (evidence of disc degeneration, disc bulging or protrusion, facet hypertrophy, or nerve root compression) and only 47% of their subjects who were experiencing low back pain had an abnormality identified[19, 20].

Pathoanatomic abnormalities are so common in the asymptomatic individual it should be viewed as a normal sign of aging with present day knowledge of MSK advanced imaging.

As it pertains to the geriatric population, a cross- sectional study revealed[17] 36% of asymptomatic persons aged 60 years or older had a herniated disc, 21% had spinal stenosis, and more than 90% had a degenerated or bulging disc [4, 17].

With 22% of the population about to cross over into the geriatric cohort, are we going to continue to expose our patients to undue radiation, opioids and costly-clinically irrelevant tests?

IV: Knowledge Translation Gaps due to…?

Minimal exposure to musculoskeletal education in medical school has previously been highlighted as a significant issue in both North America and the United Kingdom[8, 21-27].

Over the years, my physician friends and colleagues, international and domestic, have congruently agreed upon one common theme amongst their MD/DO medical education: a paucity of MSK learning opportunities during their formative years in medical school and residency training[11].

I’m fortunate to surround myself with people who are as equally as enthusiastic and curious with respect to medical learning.

My small conversational sample size over the years finally took me to the literature.

V. The Literature:

As the geriatric population continues to grow exponentially, there is an $848 billion annual fiscal estimate for treatment, diagnosis, and lost wage amounting to ~7.7% of the gross domestic product for MSK chief complaints [11, 28].

In 2030, the pediatric and geriatric population will account for 21% and 22% of our population due to the baby boomer surge[29].

Think about this for a moment. There will be more people 65 years and older than 17 years old and under.

As the geriatric population continues to stay active and educated, MSK conditions of all age cohorts are going to skyrocket. More severe forms of LBP increase with age with overall prevalence increasing until ages 60-65[19, 30, 31].

In a 2010 national study on LBP and diagnostic testing in the ED, imaging was performed in nearly 50% of all LBP patients and opioids were administered to nearly 2/3’s of the sample[7].

Emergency Medicine physician Judith Tintenalli, stated that we need increased “efforts to change consumer behaviors” with respect to patient access and referral to the ED. It has been cited that up to 43% of direct access ED visits are deemed unnecessary. When referred by a PCP, up to 44% of those referrals were also deemed inappropriate. [32]

A modification of the Tintenalli statement would be we need increased efforts to change consumer and clinician behaviors. Clearly patients and providers are both lacking awareness of who should be utilizing ED skilled clinical services for MSK conditions.

With rates of chronicity related to an episode of LBP increasing [2], there needs to be a significant shift in intervention and clinical decision making for patients of all ages.

Change in behavior, intervention, and clinical decision making?

What else is there besides the physician ordered image, oral medication, invasive procedure and surgery?

VI. The role of the Non-Physician Doctor in Modern Day MSK Management:

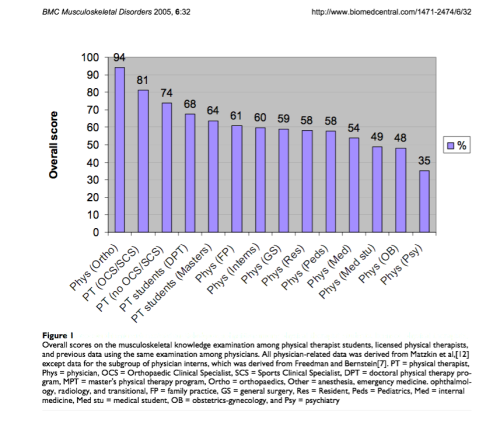

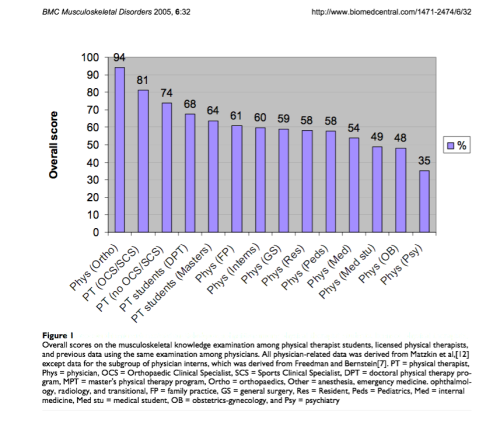

Experienced doctors of physical therapy have higher levels of knowledge in managing musculoskeletal conditions than all physician specialists except for orthopedists [6]. This includes medical students, physician interns, residents, and attending physicians.

Childs J, et al A description of physical therapists’ knowledge in managing musculoskeletal conditions. Open Access: www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/6/32

I know that piece of information was not imparted on you in medical school.

Allow me to provide some high-yield clinical pearls that will hopefully expand your breadth and depth of knowledge as it pertains to low back pain and your patients.

Who is the present day Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT)?

Simply stated, DPTs are body mechanics. Our sole purpose is to make people move and interact with their environment in the most energy efficient, symptom free, safe, and functional way.

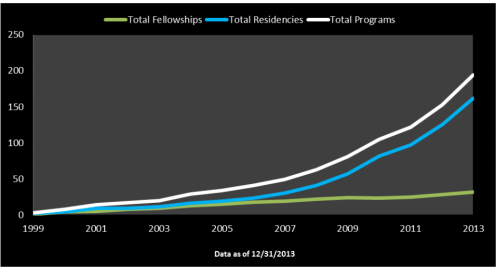

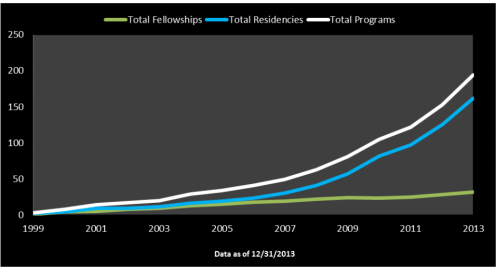

DPTs are skilled doctoral degree level clinicians with core knowledge of all systems to allow us to appropriately screen and differentially diagnose all patients that we come in contact with for evaluation and treatment. Similar to the traditional medical model, we have intensive board specialities in cardiology, orthopedics, sport, geriatrics, pediatrics, neurology and hand. Residency and fellowship are also becoming more prevalent with ~2,500 DPT’s trained in residency or fellowship from 1999-2013[33].

Accessed: www.abptrfe.org/Home.aspx

As of January 2015, all 50 states will have direct access to DPT’s. This means that a prescription is no longer required to access our care for the MSK patient.

Image: http://webreprints.djreprints.com/1715540469703.html

Direct access privileges have been present in the US Army for over 40 years. In fact, Army DPT’s are able to order imaging and administer medication as necessary.

A retrospective analysis of 472, 013 patient visits at 25 military healthcare sites, 45.1% of the visits were determined to be patients with direct access and without physician referral. No adverse events were determined from either physical therapy diagnosis or management [34].

What does direct access mean for the civilian population?

Simply stated: autonomy.

This means that patients can have instant access to a DPT as soon as they have MSK pain or dysfunction. We’ve accepted the role of greater diagnostic responsibility by achieving the clinical rigors of a doctoral education; this autonomy doesn’t mean we stop communicating with the medical community. DPT’s have worked hard to achieve autonomous practice. Working and communicating with the physician, physician assistant (PA-C), and Nurse Practitioner (NP) are still priority as our profession tends to lead the way in collective competence as we learn to adapt to today’s healthcare systems.

What’s new on the low back pain rehabilitation front?

Accessing LBP patients early is critical to improved outcomes and decreased economic, social, psychological and familial burdens. Early physical therapy (within 14 days of primary care) was associated with decreased use of advanced imaging, additional physician visits, lumbar surgery, lumbar injections, and opioid medications, as compared to delayed physical therapy [2, 35].

LBP is not a homogenous entity.

Pathoanatomic diagnoses are no longer the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute, subacute or chronic LBP. Factually, this is why many LBP studies failed to achieve anything substantial, measurable and remarkable over the last two decades (see false positive and true negative rates above).

Presently, there has been some excellent work done by Fritz[36-38], Childs[6, 39], and Delitto[19] working on sub-grouping LBP patients. If you choose to do any interdisciplinary reading these are the articles you should be reading to expand your knowledge base.

The development of classification systems has been identified as a priority among researchers in the primary care management of patients with low back pain[19, 40].

An entirely separate article can be devoted to sub-groups and treatment based classification systems; however, for immediate knowledge translation integration, I’ve identified four of the subgroups for you below.

Treatment based classification systems use an in depth history, mechanism of injury, and physical examination. They include 1. mobilization, 2. specific exercise, 3. immobilization, and 4. traction subgroups [19].

We know that LBP is not a homogenous entity, therefore, we need to identify, triage, and treat these patients differently depending on where they are along the spectrum of their dysfunction and pain episode.

Every subspecialty in healthcare is going to come in contact with a LBP patient due to the incidence, prevalence, and potential debilitating nature of the injury.

Now is the time to think differently. Now is the time to stop putting the square peg in the round hole.

In a landmark study by Daker-White et al in 1999[41], a randomized controlled trial was done comparing care of patients solely seen by the physician v. the PT. Entitled, Shifting boundaries of doctors and physiotherapists in orthopaedic outpatient departments, 244 patients were seen by a post-fellowship physician and 237 patients were seen by a physical therapist.

The results?

Patient centered outcomes in this RCT favored the PT.

Orthopedic physical therapy specialists are as effective as post-fellowship junior staff and clinical assistant orthopaedic surgeons in the initial assessment and management of new referrals to outpatient orthopaedic departments, and generate lower initial direct hospital costs. [41]

Lower costs, increased clinically relevant outcomes, and competent clinicians expediting patient care?

Ladies and gentleman, welcome to the future of healthcare.

VII. Possible solutions:

There is a scarcity of dually trained specialty board certified, residency, and/or fellowship trained doctors of physical therapy in the US; however, we do exist and there are more and more physical therapists pursuing doctoral level degrees, speciality certification, and advanced training every year.

There needs to be a healthy interaction, rapport building and conversation amongst the physician and DPT in the #MedEd community. We need your presence for prescriptive intervention for the biochemistry needs and red flags that can occur with this patient population just as much as there is a need for a paradigm shift in prescriptive, existing clinical decision making, and intervention as it pertains to the LBP patient.

Doctors of Physical Therapy have slowly been introduced to the emergency medicine team and thus far with great success[42]. As this trend continues to grow, a more immediate solution needs to occur.

All 50 states in the US will have direct access to physical therapy services in January of 2015. Now is the time to refer that patient directly to the orthopedic physical therapy office (with or without prescription) so we can decrease unnecessary ED visits leading to opioid prescriptions, imaging, and other prescriptive screening tools leading to costly downstream clinically irrelevant interventions.

Use us. No, really. Use us.

Let us safely screen and differential this cohort of patients. Most of the time they need reassurance that they will be ok and we can provide them with the screening tools to differentially diagnose and refer out to the proper physician as needed.

Most important to the patient, we can make them feel better-if not physically, psychologically usually within the first visit in order to decrease fear-avoidance behaviors[37].

Providing patient education on positioning for comfort, relief and functional positioning for their activities of daily living while utilizing our manual therapy skills to massage, mobilize, manipulate, therapeutically exercise, or stretch this population of patient is key to successful clinically relevant outcomes.

Remember, the LBP patient is not a homogenous entity and neither is their interventional prescription. Let us identify their sub-group based off of treatment based classifications and safely intervene right away (ideally within the first two weeks).

I hope this review provided some new and thought provoking ideas that will hopefully plant the seed for you to share this blog with a fellow colleague, look further in to the literature, and expand the breadth and depth of your MSK knowledge base.

My name is Dr. Jessica Schwartz. I am a residency trained Doctor of Physical Therapy. How can I assist you and your patient’s needs today?

Quick Points:

1. Physician, PA-C, and NP colleagues #ThinkDifferent and take a pause in your clinical decision thought processes when encountering your next low back pain patient. Do you know a PT that you trust and can directly refer to? Now you have excellent conversational tools to engage in a conversation in an interdisciplinary way to best suit the patients needs.

2. PT’s in the United States will have direct access in all 50 states starting January 2015. This means a patient does not need a prescription to access our services. This can be for an acute, subacute, and chronic condition. Allow us to differentially screen and refer out as needed. See the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) Overview.

3. Use this article to expand the breadth and depth of your MSK knowledge base when speaking with fellow colleagues. Think beyond the opioid, radiographic image, and the “wait and see approach”. Take action within the first 14 days of an acute episode and be participative in your patients intervention

4. To my international colleagues, please use this article to engage in conversation. I’ve already learned so much from interdisciplinary conversation after publishing this article. Question medicine…always. Engagement is how we learn and continue to grow. Cheers to you!

Bibliography

1. Hart, L.G., R.A. Deyo, and D.C. Cherkin, Physician Office Visits for Low Back Pain: Frequency, Clinical Evaluation, and Treatment Patterns from a U.S. National Survey. Spine, 1995. 20(1): p. 11-19.

2. Childs, J.D., T.W. Flynn, and R.S. Wainner, Low back pain: do the right thing and do it now. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2012. 42(4): p. 296-9.

3. Luo, X., et al., Estimates and Patterns of Direct Health Care Expenditures Among Individuals With Back Pain in the United States. Spine, 2004. 29(1): p. 79-86.

4. Chou, R., et al., Diagnostic Imaging for Low Back Pain: Advice for High-Value Health Care From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med, 2011. 154: p. 181-189.

5. Pinney, S.J. and W.D. Regan, Educating Medical Students About Musculoskeletal Problems. JBJS, 2001. 83-A(9): p. 1317-1320.

6. Childs, J.D., et al., A description of physical therapists’ knowledge in managing musculoskeletal conditions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2005. 6: p. 32.

7. Friedman, B.W., et al., Diagnostic testing and treatment of low back pain in United States emergency departments: a national perspective. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2010. 35(24): p. E1406-11.

8. Comer, G.C., E. Liang, and J.A. Bishop, Lack of Proficiency in Musculoskeletal Medicine Among Emergency Medicine Physicians. J Orthop Trauma, 2014. 28: p. e85-e87.

9. Freedman, K.B. and J. Bernstein, The Adequecy of Medical School Education in Musculoskeletal Medicine. JBJS, 1998. 80-A(10): p. 1421-1427.

10. Freedman, K.B. and J. Bernstein, Educational Deficiencies in Musculoskeletal Medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2002. 84-A(4): p. 604-608.

11. Truntzer, J., et al., Musculoskeletal education: an assessment of the clinical confidence of medical students. Perspect Med Educ, 2014. 3(3): p. 238-44.

12. Sneiderman, C., Orthopedic practice and training of family physicians: a survey of 302 North Carolina practitioners. J Fam Pract, 1977. 4: p. 267–350.

13. Chou, R., et al., Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med, 2007. 147: p. 478-491.

14. Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. [cited 2014 December 21, 2014]; Available from: http://choosingwisely.org/.

15. Ashurst, J.V., et al., Effect of triage-based use of the Ottawa foot and ankle rules on the number of orders for radiographic imaging. J Am Osteopath Assoc, 2014. 114(12): p. 890-7.

16. Wiesel, S.W., et al., A study of computer-assisted tomography. I. The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine, 1984. 9: p. 549-551.

17. Boden, S.D., et al., Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. JBJS, 1990. 72(3): p. 403-408.

18. Baliki, M.N., et al., Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain. J Neurosci, 2006. 26(47): p. 12165-73.

19. Delitto, A., et al., Low Back Pain Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2012. 42(4): p. A1-A57.

20. Savage, R.A., G.H. Whitehouse, and N. Roberts, The relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of the lumbar spine and low back pain, age and occupation in males. Eur Spine J, 1997. 6(106-114).

21. Matzin, E., et al., Adequacy of Education in Musculoskeletal Medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005. 87-A(2): p. 310-314.

22. Lynch, J.R., et al., Important demographic var- iables impact the musculoskeletal knowledge and confidence of academic primary care physicians. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006. 88(7): p. 1589-1595.

23. Day, C.S., et al., Musculoskeletal medicine: an assess- ment of the attitudes and knowledge of medical students at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med, 2007. 82: p. 452-457.

24. Queally, J.M., et al., Deficiencies in the education of musculoskeletal medicine in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci, 2008. 177(2): p. 99-105.

25. Al-Nammari, S.S., B.K. James, and M. Ramachandran, The inadequacy of musculoskeletal knowledge after foundation training in the United Kingdom. JBJS, 2009. 91-B(11): p. 1413-1418.

26. Menon, J. and D.K. Patro, Undergraduate orthopedic education: Is it adequate? Indian J Orthop, 2009. 43(1): p. 82-86.

27. Bernstein, J., G.H. Garcia, and J.L. Guevara, Progress Report: the prevalence of required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine at decade’s end. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2011. 469: p. 895-897.

28. Facts in Brief. [cited 2014 December 21, 2014]; Available from: http://www.boneandjointburden.org/highlights/FactsinBrief.pdf.

29. Hooyman, N.R. and H. Asuman Kiyak, Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Seventh ed. 2005, United States of America: Pearson.

30. Lawrence, R.C., et al., Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum, 1998. 41: p. 778-799.

31. Loney, P.L. and P.W. Stratford, The prevalence of low back pain in adults: a methodological review of the literature. Phys Ther, 1999. 79(4): p. 384-396.

32. Tintinalli, J.E., Emergency Medicine. JAMA, 1996. 275(23): p. 1804-5.

33. ABPTRFE: American Board of Physical Therapy Residency and Fellowship Education. December 21, 2014]; Available from: http://www.abptrfe.org/home.aspx.

34. Deyle, G.D., Direct access physical therapy and diagnostic responsibility: the risk-to-benefit ratio. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2006. 36(9): p. 632-4.

35. Fritz, J.M., et al., Primary care referral of patients with low back pain to physical therapy: impact on future health care utilization and costs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012. 37(25): p. 2114-21.

36. Fritz, J.M. and R.S. Wainner, Examining Diagnostic Tests: An Evidence-Based Perspective. Phys Ther, 2001. 81(9): p. 1546-1564.

37. Fritz, J.M. and S.Z. George, Identifying Psychosocial Variables in Patients with Acute Work-Related Low Back Pain: The Importance of Fear-Avoidance Beliefs. Phys Ther, 2002. 82(10): p. 973-983.

38. Fritz, J.M., J.A. Cleland, and J.D. Childs, Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2007. 37(6): p. 290-302.

39. Childs, J.D., et al., A Clinical Prediction Rule To Identify Patients with Low Back Pain Most Likely To Benefit from Spinal Manipulation: A Validation Stud. Ann Intern Med, 2004. 141(12): p. 920-930.

40. Borkan, J.M., et al., A report from the Second International Forum for Primary Care Research on Low Back Pain. Reexamining priorities. Spine, 1998. 23(18): p. 1992-1996.

41. Daker-White, G., et al., A randomised controlled trial. Shifting boundaries of doctors and physiotherapists in orthopaedic outpatient departments. J Epidemiol Community Health, 1999. 53: p. 643-650.

42. Plummer, L., et al., Physical Therapist Practice in the Emergency Department Observation Unit: A Descriptive Study. Phys Ther, 2014.