We Can Do Better: A Multidisciplinary Proactive Medical Education Push in the Management of Sports Concussion Inspired by the 2014 FIFA World Cup

By Dr. Jessica B. Schwartz PT, DPT, CSCS & Mrs. Katy Harris MS, ATC

According to a July 10, 2014 press release from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), “Physicians have an ethical obligation to ensure that their primary responsibility is to safeguard the current and future mental health of their patients” [1]. I’d like to extend this scope of practice to all healthcare practitioners, in particular, the Athletic Trainers (AT) and Sports Physical Therapists (PT) who are engaging, treating, examining and differentially diagnosing these athletes right on the sideline. Initiating conversation regarding this multidisciplinary push is apropos as the AAN just led the inaugural Sports Concussion Conference in Chicago, July 11-13, 2014, and did an excellent job discussing the multidisciplinary and multifactorial components of Concussion in Sport [2-4].

Alvaro Pereira, of Uruguay’s National Soccer Team, was the first and the most notable concussed athlete in the 2014 Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup. Pereira’s concussion was the concussion heard and felt around the world. Television newscasters and millions of people sitting in their local sports bars and living rooms around the world witnessed Pereira laying lifeless on the field after receiving a blow to the head during match play.

Unfortunately, Pereira’s concussion incident was not an isolated one during this 2014 FIFA World Cup. During the 27th minute of the Holland v. Argentina semi final, Javier Mascherano of Argentina collided heads with an opposing player losing balance and collapsing on the field. During the 16th minute of the Argentina v. Germany final, Christoph Kramer of Germany was blindsided by an Argentine player collapsing to the ground clearly dazed and in pain. Pereira and Mascherano’s concussions are of particular interest because these world class athletes were not only medically escorted off the field for examination, they returned to match play unlike Kramer who was benched for the remainder of the final.

I’d like to use the Pereira concussion incident to facilitate conversation amongst the medical community. Pereira’s concussion is of particular controversy because of his loss of consciousness (LOC), his dazed appearance, and blatant disregard for the sideline physician’s poor attempt to keep him out of the game.

Medical professionals that are a part of a comprehensive concussion management team (Physicians, Physical Therapists, Athletic Trainers, Neuropsychologists, Vision Therapists, etc) are educated that during an acute head injury where a concussion is suspected, an athlete’s cognitive ability may be transiently compromised [1]. This transient loss in cognitive ability is unsafe for the player in question as the injured athlete is often dazed, confused and displays poor kinesthetic awareness, thus making it unsafe for everyone around him or her.

World class athletes need to be represented by world class medical care. This leaves us with the glaring question that every medical professional should be asking themselves after the Pereira incident: how are we allowing players to make autonomous medical decisions during match play when they are clearly medically unstable?

If an elite professional soccer player who is visibly dazed and confused returns to play after being knocked unconscious on a world stage, what is happening at the youth, high school and collegiate levels?

Medical Presence on the Athletic Field:

In a 2014 position statement by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA): Management of Sport Concussion, Athletic Trainers should be present at every sporting event, regardless of level of play, age or sport [5].

In the United States, there are only a few states that mandate Athletic Trainers in middle schools and high schools. The timeliness of the NATA position statement coincides perfectly with the epidemic injury prevalence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears and concussions in our youth and collegiate athletes. Likelihood of an ACL injury in the female athlete is eight times [6] higher than that of their male counterparts [7] while there are 1.6-3.8 million sport-related concussions diagnosed per year [8].

Medical presence needs to become a priority for the safety of our children and athletes.

In the United States, youth coaches are often parents, volunteers, history teachers, gym teachers, athletic directors and so-on. The bottom line is that they have limited (generally a basic life support (BLS) CPR certification) to no medical background. How are we not advocating for the safety and rights of our children to have an Athletic Trainer present for all sporting events, including practices? How do we have the best medical personnel for our professional athletes and a glaring absence of coverage for our youth athletes?

Fiscal deficits are often the primary “rationale” for the lack of Athletic Trainer presence in school districts. A global educational push for parents, coaches, and school districts should be addressed with our vast and ever growing knowledge of concussion and athletic injury.

Protocol for an injured athlete for most school districts and tournaments in the state of New York is to dispatch for an ambulance via a 9-1-1 call. For non-emergent issues, this is not only a waste of precious time and resources for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and the Emergency Department (ED), it is incredibly expensive bordering fiscally irresponsible for an athlete with a non-emergent injury to go to the ED. With an average ambulance ride 25 miles or under costing $858 [9] v. an approximate rate of $35/hr or $150/match for a Certified Athletic Trainer, hiring an Athletic Trainer appears to be the most ethically and fiscally responsible long-term action step.

Our job as medical professionals is to practice with nonmaleficence (do no harm). Ethically, it can be inferred that it is our job to step in and step up for our athletes during the most intense and heated game day situations. We are always mindful of case specific scenarios with regard to a multi-billion dollar event like FIFA’s World Cup or if their is a scholarship scenario for an athlete on the line pending injury report. With respect to sport concussions, we are aware of the potential short term and long term neurological sequelae of second impact syndrome [12], repetitive head injuries and/or subconcussive blows to the body that can result in serious neuropsychological, neurocognitive, and neurobehavioral deficits [10-11].

Second Impact Syndrome (SIS) occurs when an athlete suffers from another concussion while still recovering from the initial one. While SIS is rare, it can have detrimental or even fatal effects long term if a neuroaxonal injury is repeated during a time of acute injury or during the healing stage after the neurometabolic cascade [12]. Athletes, parents, coaches and school boards need to be thoroughly educated of the potential risks of the long-term neurological sequelae that can exist post-concussion.

Subconcussive blows, impact to the body not directly contacting the head, cannot be overlooked. While they are nearly impossible to be accounted for, both animal and human research models have elicited signs and symptoms of concussion in conjunction with damage to the central nervous system causing pathophysiological changes despite an absence of acute changes in observational behavior[13-15].

Using Pereira as a talking point, although he played on during the remainder of match play and did not have another direct blow to the head, soccer is a very physical sport. Man to man contact and accidental collisions occur on the field all the time. In fact, this is part of sport. As clinicians, we are aware that post-mortem research after head injury with repeated subconcussive blows have a cumulative effect [16] and may accelerate cognitive decline leading to an altered neuronal biology later on in life [17].

Let us stop to ask ourselves and educate our players and coaches, is it worth it?

Working with athletes who have undergone neurocognitive decline is heartbreaking. The powerful documentary Head Games: The Global Concussion Crisis is a powerful movie that illustrates the elite athletes plithe with neurocognitive decline and Alzheimer’s like degenerative disease. This movie can be easily accessed and used as an educational tool for the lay public and medical professional. The carryover is excellent and provides excellent question and answer opportunities for parents, coaches, and athletes to engage with their medical professional.

Medical Education for the Clinician Working with the Concussed Athlete:

FIFA’s own concussion guidelines clearly indicates “loss of consciousness or responsiveness”, “lying motionless on ground” and “dazed, blank or vacant look” as visible clues to aide in sideline concussion identification (see image below).

Image Credit: (http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/footballdevelopment/medical/01/42/10/50/130214_pocketscat3_print_neutral.pdf)

The World Cup employs some of the top medical professionals in the world. If Alvaro Pereira was allowed to return to match play after exhibiting LOC, balance problems, appearing emotional labile, dazed and confused on a world stage, then we have some serious work to do as a medical community.

Alvaro Pereira apologized in a formal public statement to the Uruguayan physician the day after the match. Professionally, FIFA and the team physician should’ve reciprocated this apology to Pereira as it was ethically irresponsible for him to return to same day play sans rest, a full neurological and sideline evaluation. Players blatant disregard for medical opinion and feedback needs to be overridden by professional, medical, and legal protocols. Moving beyond the FIFA Concussion Recognition Tool, protocols leave no room for negotiation. Simplicity in prose, for example, if a player loses consciousness they cannot return to same day match play. Period. End of discussion.

At the youth and collegiate levels, there has been a recent push in concussion education for coaches. As of January 2014, all 50 states including the District of Columbia individually implemented youth sports concussion laws [1, 18]. On May 29, 2014, President Obama announced an initiative headed by the National Football League (NFL) and NATA to place Athletic Trainers in schools who do not currently have access to the appropriate medical professionals. Presently, only 55% of high schools have access to Athletic Trainers. It should be noted that access does not mean daily treatment and presence. Access can mean weekly visits to a school or a team. We need to do better.

As of July 1, 2014, The Indiana State Senate enforced a Bill to be the first state to require football coaches to participate in the “Heads Up” concussion training course every two years. “Heads up: Concussion in High School Sports” is a national concussion awareness initiative that started in 2005. It is a multimedia tool kit of educational flyers, videos, and fact sheets meant for coaches, parents, athletes, athletic directors and athletic trainers [19].

The implementation of individual state laws for youth sports concussion and mandating coaches participation in concussion awareness is an excellent step in a proactive direction with the safety of our athletes in mind; however, there needs to an increased focus on the medical professional and his or her role in taking charge of the athlete medically on and off the field.

It is unfair to place injury recognition responsibilities on the coach whose sole responsibility should be coaching. It is also unsafe for the player not to receive care by a certified medical professional who has the ability to differentially diagnose and identify the red and yellow flags necessary to keep the players short term and long term health and safety as number one priority.

Making a Proactive and Educated Change in Sport Culture:

A July 9, 2014 article published in Neurology discusses the paucity of skilled Neurologists who are comfortable with treating concussion [20]. It has been refreshing to work professionally with a wide array of medical professionals who have set aside ego while keeping the interest of education and patient outcomes a top priority.

Implementing multidisciplinary concussion management teams are going to be the future of fully comprehensive sport programs for athletes of all ages and abilities.

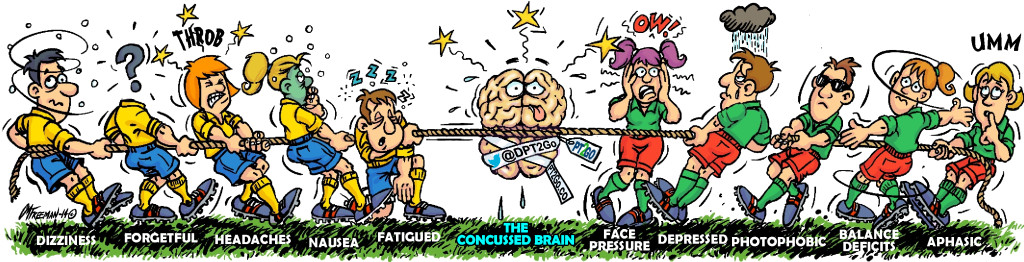

Educating ourselves as medical professionals is the first step in understanding multidisciplinary scopes of practice. Communication between a tightly knit team of Physicians, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists, Athletic Trainers, Neuropsychologists, Psychotherapists, and Speech Therapists will provide the best overall team outcomes for the concussed athlete who can experience an overwhelming array of physical, cognitive, social and emotional distress in a short amount of time.

A prime example of cross disciplinary education and interaction regarding concussion advocacy recently occurred with a colleague of mine who has the same passion for concussion advocacy and management. Katy Harris, M.S., A.T.C., is a seasoned Athletic Trainer who has a particular interest and expertise in sports concussion. She has exemplified the role of Athletic Trainer over the years with her ability to educate her athletes, coaches and parents on health and safety as it pertains to concussion.

Early in her career, Katy was the sole responsible Athletic Trainer for 400+high school and middle school athletes. While New York State does not require an Athletic Trainer in its public high schools, we need to be able to set up these qualified professionals for success and not career burn out. A common theme of frustration amongst Katy’s Athletic Training colleagues is wanting to provide the highest standard of care for all athletes, but not having access to or funding for delivering proper care combined with yearly job uncertainty due to frequent state budget cuts.

When discussing past memorable experiences regarding lack of concussion awareness amongst coaches and school districts, she immediately recalled a scenario when she happened to pass by a coach coming home from an away game. The coach informed her that one of his athletes was forcefully kicked in the head, had a headache, saw stars and was dizzy, but insisted he didn’t think it was a concussion and sent the child home. The coach dismissed the glaring prognostic indicators of a concussed athlete, not because he is negligent, but because he is not a trained medical professional. It should not be the job of a coach to make critical health decisions for his or her athletes.

When Katy was the supervising Athletic Trainer for a high school football team, she was in charge of 50+ boys at a time. If an injury was suspected or occurred, in order to reduce confusion on the field and to assert herself professionally, she would physically confiscate the athletes helmets so they were not able to return to play.

Katy’s exemplary action steps and advocacy for concussion education and management on and off the field is a lesson that FIFA’s World Cup legislators can take note of for future tournaments.

I look forward to being a part of the proactive concussion conversation in the years to come. In the mean time, lets continue to facilitate passionate multidisciplinary conversations at conferences, utilizing social media, continuing education across all professions, and accessing the medical professional at the entry level and residency components of their educational journey.

In conclusion, we can and will do better proactively educating ourselves as doctors and clinicians for the health, safety and future well-being of our athletes.

References:

- Kirschen, M. P., et al. (2014). “Legal and ethical implications in the evaluation and management of sports-related concussion.” Neurology.

- http://www.symplur.com/healthcare-hashtags/aanscc/ accessed July 14, 2014.

- https://twitter.com/search?f=realtime&q=%23AANSCC&src=typd accessed July 14, 2014.

- https://www.aan.com/conferences/sports-concussion-conference/ accessed July 14, 2014.

- Broglio, S. P., Cantu, R. C., Gioia, G. A., Guskiewicz, K. M., Kutcher, J., Palm, M., & Valovich McLeod, T. C. (2014) National athletic trainers’ association position statement: Management of sport concussion. Journal of Athletic Training, 49 (2), 245-265.

- Hutchinson, M R. (1995) Knee injuries in female athletes. Sports Med, Apr;19(4):288-302.

- Knowles, S. B. (2010). “Is there an injury epidemic in girls’ sports?” Br J Sports Med 44(1): 38-44.

- Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. (2006) The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 375–378.

- Delgado, M. K., et al. (2013). “Cost-effectiveness of helicopter versus ground emergency medical services for trauma scene transport in the United States.” Ann Emerg Med 62(4): 351-364 e319.

- Shuttleworth-Edwards AB, Radloff SE. (2008). Compromised visuomotor processing speed in players of Rugby Union from school through to the national adult level. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 23:511–520.

- Wall SE, Williams WH, Cartwright-Hatton S, et al. (2006). “Neuropsychological dysfunction following repeat concussions in jockeys.” J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77:518–520.

- Weinstein, E., et al. (2013). “Second impact syndrome in football: new imaging and insights into a rare and devastating condition.” J Neurosurg Pediatr 11(3): 331-334.

- Dashnaw ML, Petraglia AL, Bailes JE. (2012). “An overview of the basic science of concussion and subconcussion: where we are and where we are going.” Neurosurgical FOCUS 33(6).

- Bauer JA, Thomas TS, Cauraugh JH, Kaminski TW, Hass CJ. (2001). “Impact forces and neck muscle activity in heading by collegiate female soccer players.” J. Sports Sci 19(3):171-179.

- Talavage, T. M., et al. (2014). “Functionally-detected cognitive impairment in high school football players without clinically-diagnosed concussion.” J Neurotrauma 31(4): 327-338.

- Shultz SR, MacFabe DF, Foley KA, Taylor R, Cain DP. (2012). “Sub-concussive brain injury in the Long-Evans rat induces acute neuroinflammation in the absence of behavioral impairments.” Behav Brain Res 229(1):145-152.

- Broglio SP, Eckner JT, Paulson HL, Kutcher JS. (2012). “Cognitive Decline and Aging: The Role of Concussive and Subconcussive Impacts.” Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev 40(3):138-144.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Traumatic brain injury legislation. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/ health/traumatic-brain-injury-legislation.aspx. Accessed June 3, 2014.

- Sawyer, R. J., Hamdallah, M., White, D., Pruzan, M., Mitchko, J., & Huitric, M. (2010). “High school coaches’ assessments, intentions to use, and use of a concussion tool kit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Heads Up: Concussion in High School Sports.” Health Promotion Practice, 11 (1), 34-43.

- Deibert, E. (2014). “Concussion and the neurologist: A work in progress.” Neurology.

Very good post. I absolutely love this website.

Stick with it!